A pianist’s left hand. So often, it can be the Achilles Heel of pianistic technique. And while classical pianists often have a much stronger left hand than jazz pianists by comparison (as a gross generalization), ask any pianist and they’ll most likely tell you that they wish their left hand was “stronger.” But what exactly does that mean?

Technique or “strength” in a hand really comes down to just two things: 1) Rhythmic clarity AND 2) Rhythmic independence (in the fingers)

Why the stress on rhythm? Don’t worry, it’s not all about playing lots of fast notes. Because the piano is a percussion instrument, the tone of the instrument is dependent on how we both attack and release the key. In other words: speed into the key and speed out of the key. Think of rhythm as having both vertical and horizontal components. So often, when we think technique, we focus on the horizontal component of rhythm: moving from one note to the next. But there’s so much more: how we enter the key, how we release it, how we prepare all of that, etc. But it all comes back to rhythm.

FIRST, try this:

How many different tones/colors can you get on one note with your left hand pinky? 4th finger? 3rd? 2nd? Thumb? Shoot for at least 15 per finger!

I find Hannon exercises boring. I find actual music stimulating. So, I figured, why not use real music as a vehicle for improving the technique of my left hand (specifically). Though I am originally classically trained and have played a fair bit of the standard classical repertoire, I’m always looking to get better at every aspect of my musicianship. Technique is so important to me because of what it can lead to, not what it represents in isolation. Fast notes mean nothing unless there is intent behind them. Think of improving your pianistic technique like a great speaker would improving on diction, vocabulary, or grammar. These things mean very little until that speaker decides what he’s going to say. But if he didn’t have those tools, he’d be limiting himself.

I had a chance to work with Felix Pastorious a few years back, and to this day, I think his definition of technique is the best I’ve heard: “Technique is what you need to do to consistently produce the sound you want without hurting yourself.” Think about that…

Here are FOUR creative approaches I’ve taken to drastically improving my left hand in under a year:

1) Practice solo lines in unison

There was a point in my playing about a year ago where my left hand sounded so bad whenever I’d try to improvise a line with it, that I almost entirely gave up on left hand improvisation. Luckily, there was a solution. As a starting point, try playing a solo line (could be a passage in a Bach Prelude or Fugue, a Chopin Etude, or a transcription of Coltrane or Bird) with both hands at the same time, an octave or 2 octaves apart. I practiced countless Charlie Parker Omnibook transcriptions this way. There were 2 big benefits to that approach. 1) Because Bird was a saxophonist, his lines didn’t inherently favor the R.H. As a result, both hands started from the same neutral point since the creation of the lines hadn’t considered what was “pianistic” or not. 2) Doing it this way really illuminated just how much more quickly my right hand solved the problem of fingering on the spot than my left hand. (I say “right hand or left hand” but of course, it’s really my brain making these decisions. To get really technical, quite simply, the neuropathways forged in my brain were much, much stronger for solving the issue of R.H. fingering on the fly just because I did it more!)

Practicing just the left hand on its own is effective, but practicing hands together is advantageous because you will most likely have a guide in your R.H. You’re constantly aware of what the standard is and won’t get frustrated as quickly.

2) Practice Playing melodies in your left hand

It’s easy to “hear” with your right hand if you’re not accustomed to (even sometimes) prioritizing your listening to the L.H. Practice playing melodies in your left hand to develop your ear and in a sense, recalibrate how you listen. Melodies can be taken from a Chopin nocturne, a jazz standard, or a top-40 hit…or anything else! Be creative with how you practice. If you’re not at least somewhat enjoying yourself, the practice session won’t be as sustainable or as enticing to come back to.

When playing melodies in your left hand, focus on rhythmic clarity and a lyrical tone. How would it sound if you sang it? The more and more you do this, the more lyrical independence you’ll develop in your L.H. giving you a wider palette of colors to choose from whenever you play. If you find that you’re having trouble with this, play the melody in your R.H. a few times or even sing it. Listen to a recording of that melody and think of all the different ways that you can emulate the subtleties of tone, time, articulation, etc. with your L.H. Focus on the details! Pretty soon, they’ll be automatic.

As a bonus, try improvising in your L.H. This might be a technique best suited for jazz pianists or people who are comfortable improvising in general. Make sure you have a metronome on to give yourself an honest sense of the pulse. (All 4 beats are fine, 2 & 4 is better, randomly occurring is best! :-) This is something I’ll cover in a separate article about how I use the metronome). For example, take a jazz standard like “Autumn Leaves” and improvise with just your L.H. Most likely, you’ll find that you’re hearing things that you’re unable to play cleanly. Slow it down until what you hear matches up with what you can play. Then slowly increase the tempo. As that becomes more and more comfortable, try comping with your RIGHT HAND. You may have to slow down the metronome again… :-)

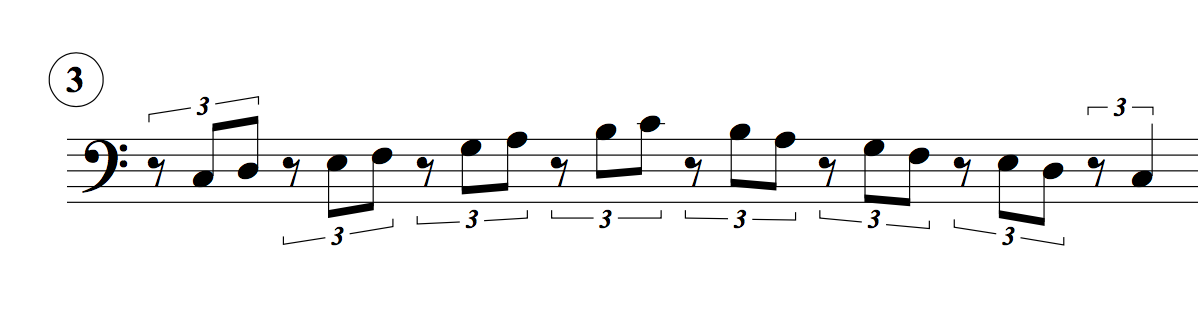

3) Practice scales hands together with a metronome, BUT…

Focus on the rhythmic clarity and tone first and foremost. It’s easy to play linear rhythms (that is, a constant stream of eighth notes, triplets, sixteenths, etc.) It’s a LOT harder to control a rhythm like a [dotted 8th – 16th] pattern or a classic “swing” rhythm. See below for a few examples. It’s also a lot harder when you don’t play on strong beats.

The reason this is so effective (and difficult) is that we’re focusing on the subtle fine motor skills in your fingers. In essence, you’re improving your rhythmic reaction time. Your left hand is likely a little less reactive than your right hand. Have you ever been frustrated playing a 3 or 4 octave scale at a fast tempo with your left hand? Yet, when you play just an octave it’s fine. That’s because your L.H. (of course, it’s really the part of the brain controlling the L.H. motor skills) takes more time to react to anything than your R.H. might. By practicing “off the beat” as seen in Examples 3 &4, we’re zeroing in on this issue and addressing it head-on.